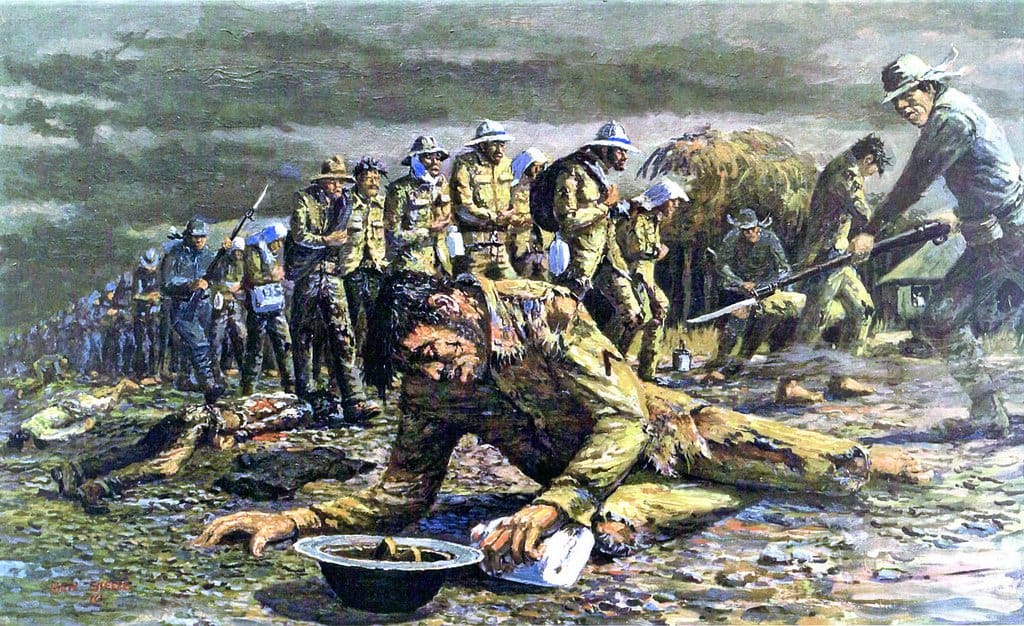

One of the worst war crimes of the 20th century began on the grounds of an elementary school in a small town in the Philippines. At the same time, one of the best military survival stories in history began. The most important part of the Bataan World War II Museum, located behind Balanga Elementary School, is a life-size model of the day U.S. troops in the Philippines surrendered to Japanese leaders on April 9, 1942.

The museum itself is very small. It takes up just two floors of a building that these days looks about the size of a modern American neighborhood house. There is wall art with bullet holes from World War II and the fighting in the Philippines, as well as wreckage and weapons from the Battle of Bataan. The model is just around the corner.

It seems not enough to remember that it was the largest defeat of US troops in history. Tens of thousands of Filipino and American soldiers began the death march from Bataan hours after the Japanese surrendered. It was a five-day, 65-mile walk to a prison camp in the north, during which they were given no food or water and it was very hot. Many people would die. Others would be incredibly strong.

Bataan’s Battle

On December 7, 1941, Japanese aircraft attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. At the same time, Tokyo forces launched their first attacks on other US military bases in the Pacific. The Philippines was one of the main destinations. When the Philippines was a U.S. colony, there were approximately 20,000 U.S. troops stationed. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enlisted about 100,000 Filipinos in the U.S. Army. Together they were called the United States Army in the Far East (USAFFE).

Japan’s first air raids took place on December 8, 1941. Two weeks later, on December 15, 1941, the main invasion force landed on Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. In just over three months, they pushed the U.S. and Filipino defenders onto the Bataan Peninsula, which lies across Manila Bay from the Philippine city. The plan of the U.S. leader in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, called for his troops to remain in the southern part of the peninsula until the U.S. Navy could send more troops and supplies to aid the beleaguered defenders.

However, Americans and Filipinos quickly ran out of food, medicine and ammunition. General Edward King, in charge of Bataan, defied his boss and ordered his men to lay down their weapons, taking full responsibility for the loss.

“Men, remember.” You didn’t give up… “You had no choice but to do what I said,” he said. According to reports from the time, King asked Colonel Matoo Nakayama, the Japanese officer who accepted the surrender, to promise that his men would be treated with respect.

The Japanese said, “We are not barbarians.” According to a trial set to take place after the war, General Masaharu Homma, who led the Japanese troops at the Battle of Bataan and was responsible for the men who carried out the death march, committed war crimes . It happened in 1946.

The march to death

The place where the people of Balanga gave up is not the place where the Bataan Death March began. Some of the soldiers came from Bagac on the west coast and Marileves on the southern tip of the peninsula. But on the way north they all passed Balanga.

The route of the march now looks like a road that could be found anywhere in the world. In the Philippines, trucks, cars and the ubiquitous motorized tricycles and jeepneys that serve as public transportation share the road. It’s about McDonald’s and Jollibee restaurants, shopping malls and car parks, farmland and housing projects that are still under construction but promise the latest in high-end living at prices most people can afford. But in 1942 it was hell on earth.

A history book about American and Filipino prisoners of war states that they were divided into groups of 100 men each, with four Japanese guards in each group. Their steps were four meters wide because it was “blazing hot” outside. In an interview with Air Force News Service in 2012, survivor James Bollich spoke about how painful it was. “They beat us with clubs, rifle butts, cutlasses and anything else they could find.” It went on like this all day. Bolich said, “They didn’t allow anyone to drink water or rest, and they didn’t give us anything to eat.”

“As soon as someone fell, the Japanese killed them,” he said. “It looked like they were setting us all on fire.” Today, there are white concrete markers along the road to commemorate the people who walked the path. For example, at kilometer 24 it says “JB McBride and Tillman R. Rutledge, two friends who marched the Bataan Death March.” At kilometer 100, in front of the military cemetery at the former US Air Force Base Clark, there is a sign that just says “Death March”. stands.

Death in a boxcar

For the thousands of US and Filipino prisoners of war, the journey from Bataan to the prison at the old US military camp Camp O’Donnell in Capas in the north of the peninsula was not just on foot. The prisoners of war were crammed into boxcars as they traveled about 30 miles (48 kilometers), from one train station in San Fernando to another about 5 miles from the prison camp.

The smallest of these freight cars had around 22 square meters of space. The wooden sides, metal panels, and small openings for air circulation turned them into ovens for the 100 or more prisoners of war who lived in each individual oven.

The last of its kind is at Capas National Shrine, built on the site of Camp O’Donnell but would be easy for a tourist to miss. Beyond the parking lot is the huge memorial to the war dead of the Philippines. The boxcar now has a roof, not in 1942. In March 2024, it is almost a safe place to escape the hot sun.

But on a plaque nearby are the stories of people who experienced a boxcar, perhaps this one, in 1942. It’s eerie to be near him, to poke your head through the open door and think about how terrible it must have been inside.

“We were shoved into crowded boxcars like animals preparing to be killed…Men struggled, trying to stay on our feet and stand upright…”The boxcar platform was a sea of filth from people suffering from dysentery suffered.” And even more.

“We melted alive in a 110-degree oven; we were shaking, spitting, peeing and pooping.” I saw some people pass out but had nothing to land on… I don’t know how many of my friends died in that car, but at least ten must have died . But for the POWs who were still alive, there was even worse to come.

Capas was a concentration camp

On the site of the former Camp O’Donnell, it’s hard to imagine what it was like when it was a prisoner of war camp and conditions were so bad that Filipinos now call it the Capas concentration camp.

The 133-acre site is home to more than 31,000 trees, each with a white number on it to commemorate the people who died in the Death March. A 70 meter high column stands over stone walls engraved with the names of the dead. It’s quiet on this March morning and I’m the only one who’s come to the snack and gift stand.